8.510 afbeeldingen

sorteren op:

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

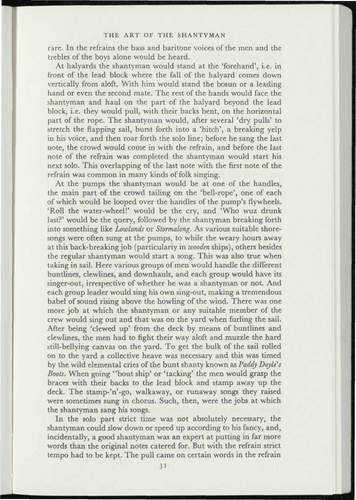

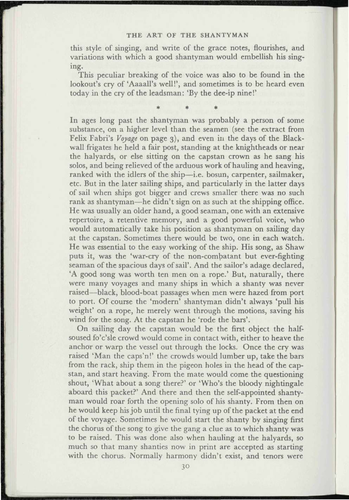

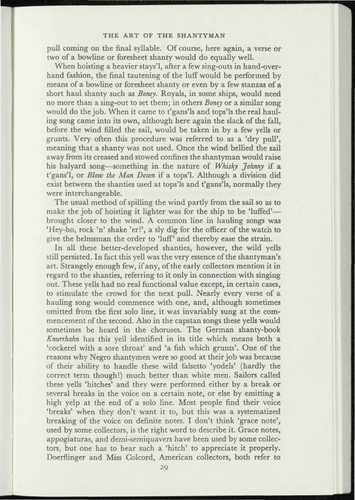

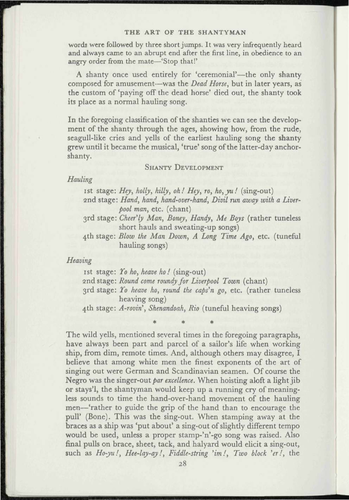

Shanties From The Seven Seas,

Titel:

Shanties From The Seven Seas

Naam uitgever:

MYSTIC SEAPORT MUSEUM

Jaar van uitgave:

First Published 1961

Taal:

Engels

Aantal pagina's:

430

Plaats van uitgave:

Connecticut

Auteur:

Collected by Stan Hugill

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Shanties From The Seven Seas,

Titel:

Shanties From The Seven Seas

Naam uitgever:

MYSTIC SEAPORT MUSEUM

Jaar van uitgave:

First Published 1961

Taal:

Engels

Aantal pagina's:

430

Plaats van uitgave:

Connecticut

Auteur:

Collected by Stan Hugill

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Shanties From The Seven Seas,

Titel:

Shanties From The Seven Seas

Naam uitgever:

MYSTIC SEAPORT MUSEUM

Jaar van uitgave:

First Published 1961

Taal:

Engels

Aantal pagina's:

430

Plaats van uitgave:

Connecticut

Auteur:

Collected by Stan Hugill

Voorbeeld : Klik op de tekst voor meer

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

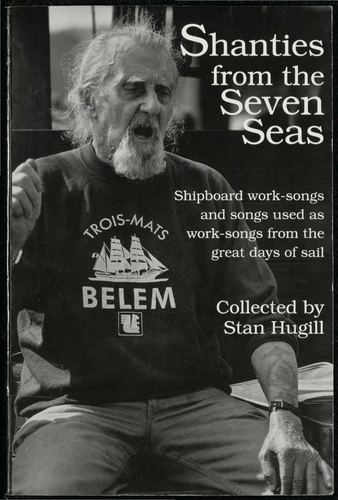

049 Shanties From The Seven Seas

Shanties From The Seven Seas,

Titel:

Shanties From The Seven Seas

Naam uitgever:

MYSTIC SEAPORT MUSEUM

Jaar van uitgave:

First Published 1961

Taal:

Engels

Aantal pagina's:

430

Plaats van uitgave:

Connecticut

Auteur:

Collected by Stan Hugill

Voorbeeld : Klik op de tekst voor meer

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

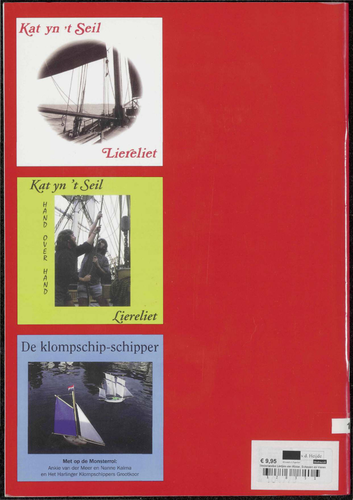

056 Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen,

Titel:

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Naam uitgever:

Windrose Music

Jaar van uitgave:

2004

Omschrijving:

Verantwoording

Aantal pagina's:

48

Paginanummer:

48

Taal:

Nederlands

Plaats van uitgave:

Drachten NL.

Auteur:

Ankie Van Der Meer & Nanne Kalma, Liereliet En Kat Yn 't Seil

Voorbeeld : Klik op de tekst voor meer

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

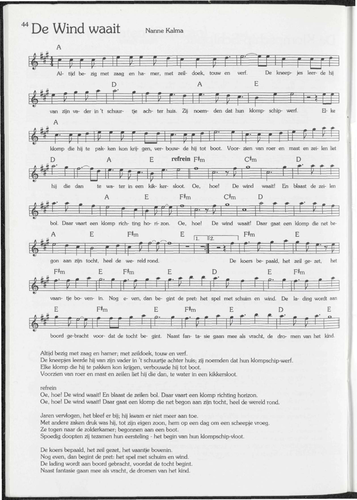

056 Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen, De Wind Waait

Titel:

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Ondertitel:

De Wind Waait

Naam uitgever:

Windrose Music

Jaar van uitgave:

2004

Omschrijving:

Bladmuziek en Liedtekst

Taal:

Nederlands

Aantal pagina's:

48

Paginanummer:

46

Plaats van uitgave:

Drachten NL.

Auteur:

Ankie Van Der Meer & Nanne Kalma, Liereliet En Kat Yn 't Seil

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

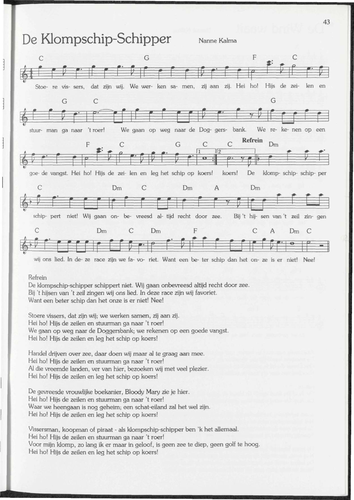

056 Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen, De Klompschip-Schipper

Titel:

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Ondertitel:

De Klompschip-Schipper

Naam uitgever:

Windrose Music

Jaar van uitgave:

2004

Omschrijving:

Bladmuziek en Liedtekst

Taal:

Nederlands

Aantal pagina's:

48

Paginanummer:

45

Plaats van uitgave:

Drachten NL.

Auteur:

Ankie Van Der Meer & Nanne Kalma, Liereliet En Kat Yn 't Seil

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

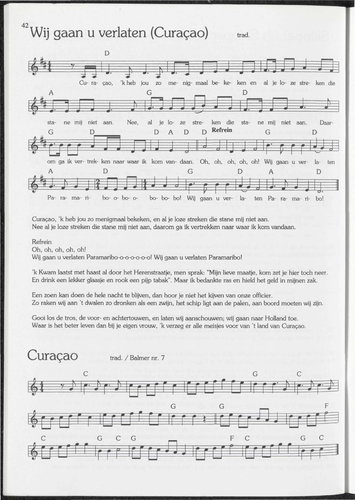

056 Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen, Wij Gaan U Verlaten (Curacao)

Titel:

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Ondertitel:

Wij Gaan U Verlaten (Curacao)

Naam uitgever:

Windrose Music

Jaar van uitgave:

2004

Omschrijving:

Bladmuziek en Liedtekst

Taal:

Nederlands

Aantal pagina's:

48

Paginanummer:

44

Plaats van uitgave:

Drachten NL.

Auteur:

Ankie Van Der Meer & Nanne Kalma, Liereliet En Kat Yn 't Seil

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

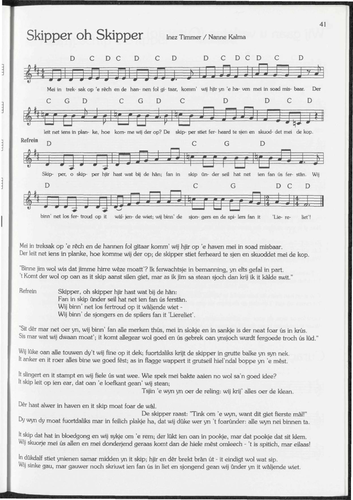

056 Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen, Skipper Oh Skipper

Titel:

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Ondertitel:

Skipper Oh Skipper

Naam uitgever:

Windrose Music

Jaar van uitgave:

2004

Omschrijving:

Bladmuziek en Liedtekst

Taal:

Fries

Aantal pagina's:

48

Paginanummer:

43

Plaats van uitgave:

Drachten NL.

Auteur:

Ankie Van Der Meer & Nanne Kalma, Liereliet En Kat Yn 't Seil

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

056 Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

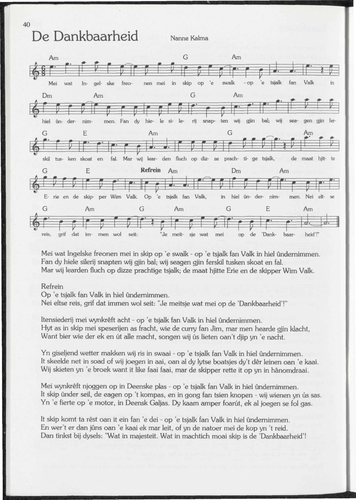

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen, De Dankbaarheid

Titel:

Nederlandse Liedjes Van Water Schepen En Varen

Ondertitel:

De Dankbaarheid

Naam uitgever:

Windrose Music

Jaar van uitgave:

2004

Omschrijving:

Bladmuziek en Liedtekst

Taal:

Fries

Aantal pagina's:

48

Paginanummer:

42

Plaats van uitgave:

Drachten NL.

Auteur:

Ankie Van Der Meer & Nanne Kalma, Liereliet En Kat Yn 't Seil

Organisatie: Shanty Nederland

laatste wijziging 07-02-2023

1 gedigitaliseerd

Mijn Studiezaal (inloggen)

Mijn Studiezaal (inloggen)